What do hamsters, ice hockey rinks, Buddhist temples, cruise ships and choirs tell us about COVID? The answer is that they are all clues in the most important investigation currently being conducted into this new disease.

Forget how we can treat it, or how we can vaccinate against it. None of this is really important if we can get to the bottom of one simple question: How do we get it? Because if we can cut the chains of transmission, we can control the epidemic – as other countries have done, from Vietnam to me New Zealand.

Of course, we’ve known the broad outlines of the Covid transmission from the start. While the effects of the virus are horrifically unusual, the primary ways it spreads are classic, says Vincent Munster, who runs Rocky Mountain Laboratories, who is modeling virus behavior at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“Act as if you were expecting a respiratory infection to act,” he says. Just like influenza, coughing and sneezing spread this disease. There are three classic modes of transmission to think about: through surfaces, through the air, and through close contact. However, in the ten months that have passed since the outbreak of the pandemic, our precise understanding of these three vectors has evolved and changed, and most importantly, their significance in transmission. So what do we know today about catching and transmitting Covid, and what lessons can we learn to stop it?

Surface spread was exaggerated

At the beginning of the outbreak, surface transmission appeared to be very important. Remember your frequent focus on hand washing? And in a world where people still touch and shake hands, it made sense. It was scary.

Reports from that infamous early group on board The Diamond Princess cruise ship Traces of the virus were found 17 days after his evacuation. However, what was actually found was viral RNA – bits of genetic material, apart from live virus droplets that are still strong enough to infect people.

Today, much less importance is attached to the idea that the virus can be transmitted across surfaces, known in medical terms as “fomites.” Even by summer, the World Health Organization noted: “Although there is consistent evidence of SARS-CoV-2 contamination of surfaces and the persistence of the virus on certain surfaces, there are no specific reports directly proving fomite transmission.”

This may be due to their ability to be retracted once they are out in the open. A study by the Munster team showed that the virus can survive on plastic and stainless steel for three days, one day on cardboard, and four hours on copper. But every passing moment destroys her ability to infect.

“The viability of a true live virus degrades very quickly,” says Munster. “After eight hours, you lose half of the infectious virus.” Surfaces are believed to be the least important of the three classic modes of transmission. But the time it took to learn this will have lasting effects. There are no known cases of Covid-19 being transmitted via banknotes or coins, for example. But that did not stop the rapid transmission of contactless payments and hastened the death of the cash.

Half of all transmission occurs at home

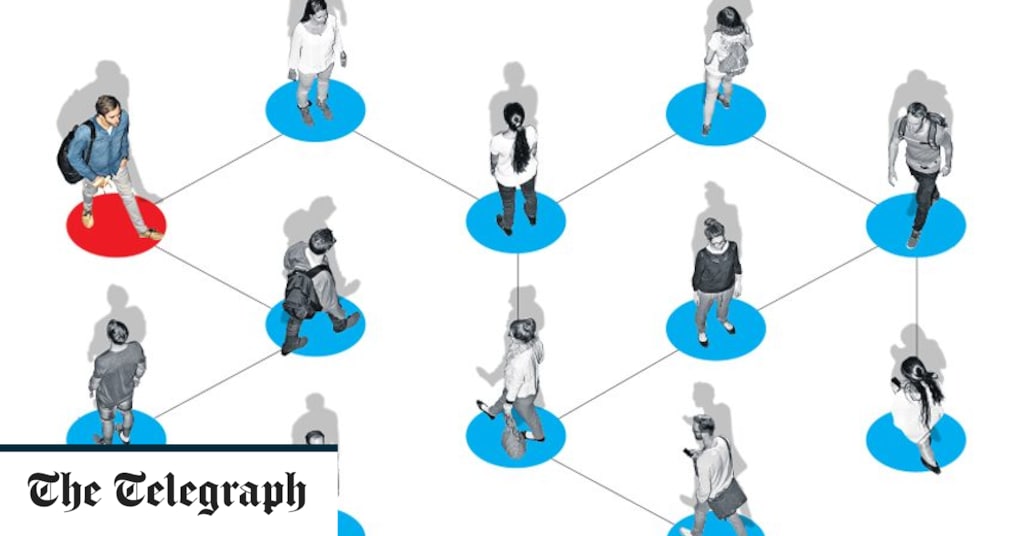

Munster says the biggest risk of transmitting the coronavirus remains close contact. “This is definitely supported by the experimental work that we’re doing here in the lab.” Healthcare workers, for example, are seven times more likely to have a positive Covid test result than non-essential workers.

A study in Sweden found that the job with the most risk is a taxi driver: 4.8 times higher than the average for all occupations. Bus drivers came next. This also helps explain why the majority of Covid infections occur in our homes and other residences where a constant close-up interaction is inevitable – like care homes.

A South Korean study found that those who live with an infected person are six times more likely to be infected than the patient’s closest contact outside the home. Studies looking at contact tracing data indicate that worldwide, more than half of all transmissions occur at home – putting older people in multi-generational families at risk. Other places where people live together – prisons or homeless shelters – are equally vulnerable.

The percentage of those infected in any outbreak is known as the attack rate. Outbreaks in care homes, prisons and shelters have recorded attack rates of up to 80 percent. Individual sensitivity is also crucial. It also comes down to getting it in a severe or moderate form.

In one study, two hamster cages – one infected and one uninjured – were placed side by side. Some of the uninfected were protected by surgical mask sections. Two-thirds of those who did not become infected, compared to only a quarter of those infected. This quarter was well below the disease.

Superfluous secrets

It is clear that sneezing or coughing by someone who carries the virus is an excellent way to catch the infection. But studies have confirmed that the virus can remain floating in the air upon exhalation. “If you’re outside, it eases off instantly,” says Munster. “If you are in a well-ventilated room, the airflow will pick up these particles and push them away. But if you are in a room without ventilation, there will be no great amount of dilution or transmission of virus particles, so the possibility of transmission will be high.”

There are several now known cases of this occurrence. Take for example the 61-member choir in Washington State, USA, 52 of them who fell sick after a two-hour training – singing warmly in a confined space was perfect for broadcast. In China, one such outbreak was described in a restaurant in detail. The virus spread from an infected restaurant to nine other people, all of whom sat under an air conditioner hatch that recirculated the air over and over again. Sixty-eight other diner-goers and eight waiters survived the infection, and it is almost certain that their mere transitory contact with floating virus particles was much less dangerous.

In some cramped places, it seems there is no escape. In January, two buses transported 128 passengers to a Buddhist temple in China. It was found that a passenger on the second bus was infected and transmitted the virus to 24 others on the bus. No matter how far they were seated on the original “index patient” on the bus. They were all close enough.

This new understanding is very important. This means that masks and plastic screens in many public places may seem more effective than they really are. An airy restaurant, filled with unmasked people from many different places, all talking out loud, is a hugely popular event waiting to happen, no matter how much plastic is deployed. No wonder that Public Health England recently found that in those who had tested positive for the virus in the past two months, “eating out was the most common activity in the two to seven days before symptoms appeared.” Last week, research researched what one economist suggested in The University of Warwick says the government’s plan to eat to help out could be responsible for five clusters of new coronavirus cases in the summer. So we have to eat outside where we can (once social contact resumes after the second shutdown), and restaurants have to turn off the bleeding musk that makes us all raise our voices.

So we should eat out wherever possible, and restaurants should shut down the mozak that makes us all raise our voices. It’s the environment, not the person, it’s superpowers But some studies suggest that only 10 percent of people may be responsible for 80 percent of infections.