There are many indications that future economic growth will be lower, and perhaps not at all. In this case, it will become more important to equitably share the income generated – as Kate Raworth writes in the book “The economics of obwarzanek. Seven ways to think about the twenty-first century economy“.

This book was included by the Financial Times (its English title is “Donut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist”) on the list of the best economic publications of the year. One Guardian reviewer saw the feelings of reading this book as comparable to those experienced by early readers of John Maynard Keynes. The book was also on The Sunday Times bestseller list. And in the largest online bookstore, amazon.com, it increased by up to 82 percent. Reviewers gave it a five star rating out of five. Is the enthusiasm of readers and journalists justified?

In the publication, the author describes how in the 1950s Robert Solow, called the father of economic theory, tried to find out why the American economy had grown over the past half century. He believed that the increase in GDP was due to increased productivity resulting from the fact that capital and workers worked together more efficiently. Create a model to test this hypothesis.

In the publication, the author describes how in the 1950s Robert Solow, called the father of economic theory, tried to find out why the American economy had grown over the past half century. He believed that the increase in GDP was due to increased productivity resulting from the fact that capital and workers worked together more efficiently. Create a model to test this hypothesis.

However, when he introduced data from the US economy into the model, it turned out that capital invested in terms of number of employees explained only 13 percent. The economic growth of the United States in the last forty years. Another economist, Musa Abramovich, whose calculations gave results similar to those of Solow, stated, “It confirms our ignorance of the causes of economic growth.”

In 2009, physicist Robert Ayres and environmental economist Benjamin Warr decided to build a new model for economic growth. They added to the classic duality of labor and capital a third factor – energy, more precisely a part of the total energy that can be used for productive work (rather than wasted as unused heat).

For the model, they used data from the 20th century on the economic growth of the USA, Great Britain, Japan and Austria. It turned out that this model explained the reasons for the growth of GDP in the above-mentioned countries. So what Solow suspected may be that as a result of technological progress turned out to be the increased efficiency with which energy is converted into useful work. What is the conclusion?

Well, the last two centuries of exceptionally fast GDP growth is due to the availability of cheap fossil fuels. It is worth realizing that the energy contained in a gallon (about four liters) of crude oil is equivalent to 47 days of hard, human and physical work. In other words, the work done by the oil we burn every day is equivalent to the work done by the multitudes of workers.

According to the author, in the future, with little or no economic growth, the redistribution of productive wealth will become more important. Incidentally, I noticed that in the twentieth century the prevailing theories were that large inequalities were necessary for the most talented incentive to invest and create that would benefit everyone, including the poor. Meanwhile, these theories are not confirmed by practice, because there are many rapidly developing countries where the disparities are small.

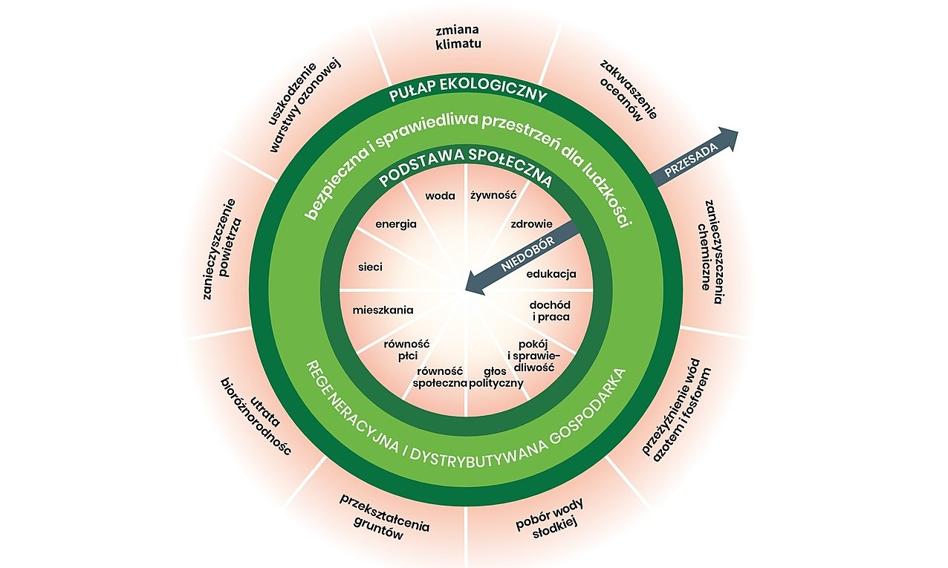

The conviction to pay more attention to redistribution is just one of the guiding ideas that, according to the author, must be driven by twenty-first century economists. There are seven principles she presents in the form of two circles that form something like an American donut with a hole in the middle (the title “Donut”).

The Seven Principles replace one-dimensional economic thinking as a means to achieve the highest possible economic growth. There are undesirable phenomena inside the donut that we want to eliminate through the economic policy of the twenty-first century (extreme poverty, lack of access to water, etc.).

On the other hand, outside of the donut, we have an area where economic growth destroys the environment. Thus, the task of economists is to pursue a policy of “the donut”, that is, that which aims to satisfy the basic needs of all the inhabitants of the Earth without destroying the environment.

The biggest weakness of Raworth’s book, in my opinion, is the lack of fresh and revealing content. The biggest feature of this publication is an attractive, i.e. graphic, in the form of a donut title, a way of presenting and summarizing what has been written in many other books.

Raworth refers to nearly every major economic work of recent years: from Marianna Mazzucato’s “Enterprise State” to Thomas Piketty’s “XXI Capital”. The concept of the economics of self-donation is interesting and noteworthy, but a dozen or so pages of articles are enough to discuss it.

So Raworth’s book can be of interest primarily to those who are not familiar with the most recent works in widely understood economics and want to spend a little time gaining a quick knowledge of the most popular topics. Others can forgive them.

It is also worth getting close to excerpts from the reviews you quoted and putting them on the cover by the publisher. Certainly, this book is not as important as, for example, Thomas Piketty’s Capital of the XXI Century, mentioned by the same author.

On the other hand, it is interesting that “Oparzanik Economics” is another “recognized” economic book that advocates greater redistribution of income by the state and increased efforts to reduce inequality.

Alexander Pinsky