A recent study by scientists from the University of Oslo in Norway and Ritsumeikan University in Japan showed that the human eye adapts better to optical illusions than we thought until now. The new kind of illusion they developed can affect our brain to the point that just looking at it makes the pupil react.

Most of us have experienced optical illusions – images that trick our brains. Parallel lines that appear curved, perspective distorted distances, or objects that appear to be moving — many of these illusions take advantage of the properties of our eyes. Recent research has shown that the eyes react to certain illusions in unexpectedly complex ways.

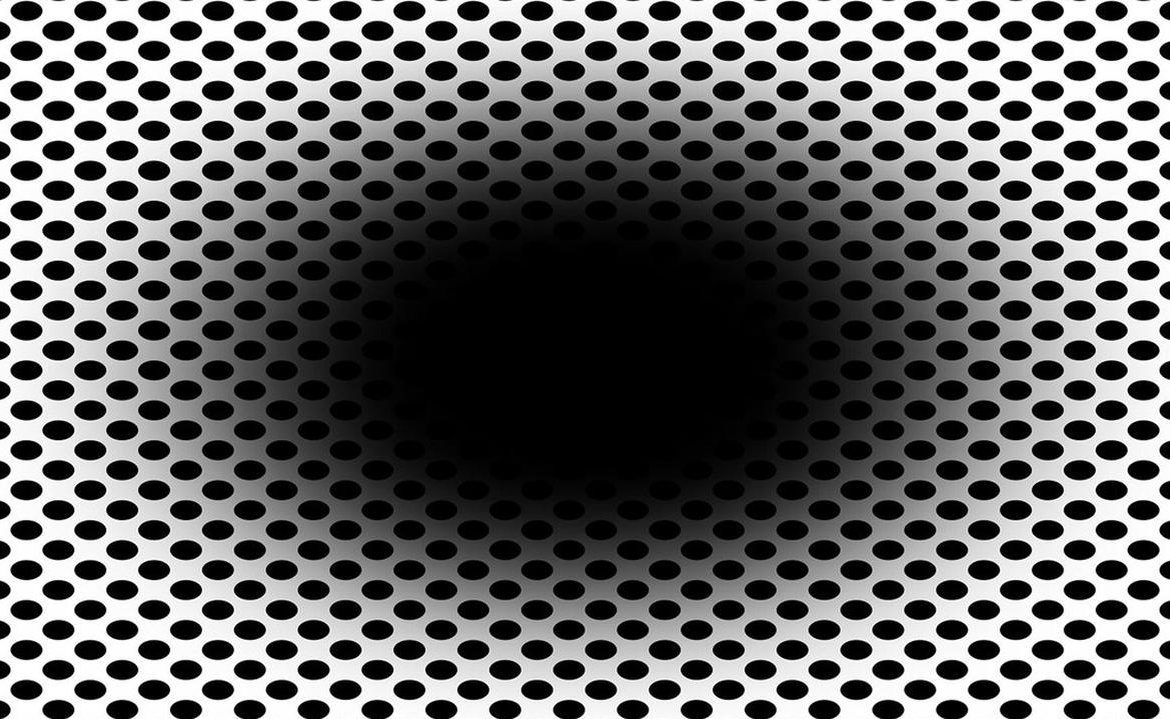

The image gives the impression that it is “expanding”twitter.com/AkiyoshiKitaoka

Journey into a black hole

The research subject was still images with a black, white, or colored central element placed on a light or dark background. The graphics are designed in such a way that they give the impression of “expanding” upon closer examination. In contrast to the classic static optical illusion, this type of illusion is not yet known to science.

The images were shown to 50 volunteers with good eyesight. The researchers recorded the participants’ reaction to each image by measuring the degree of pupil dilation before and after the selected image was presented. Volunteers were also asked to rate the speed and degree of delusion “spread”.

Analysis of the results indicated that the eyes of most participants were clearly responsive to optical illusions. The biggest changes were due to the black dots. The authors say their apparent motion gave people the impression they were “traveling inside a black hole,” causing the pupils to dilate. The brain reacts completely differently to white and colored dots on a dark background, causing the pupils to “spread out” a little, as if a faint light was shining on the participants’ eyes.

One of the visible “black holes” twitter.com/AkiyoshiKitaoka

It’s all a matter of perception

As the researchers noted, most study participants were able to notice an illusion. 86 percent of volunteers recorded clear movement in the picture using a black element, and 70 percent – in color graphics. In the case of “black holes,” the researchers observed another regularity: the more participants thought the illusion was “widening,” the more the diameter of their pupils changed.

According to Bruno Laeng, the study’s lead author, the findings “shed new light” on how vision works.

The eye adapts not only to the physical energy of light, but also to how we perceive or perceive light – says the scientist.

The researchers stress that future research into optical illusions may reveal other types of physiological changes that will allow us to understand how optical illusions work.

color optical illusiontwitter.com/AkiyoshiKitaoka

Frontiers in human neuroscience

Main image source: twitter.com/AkiyoshiKitaoka