As the Corona virus clings to, and reassert, itself in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, the hopes and fears of politicians, scientists and the rest of humanity center on the relatively small number of vaccines currently in development.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are 182 vaccines in the works, but only nine of them are currently being evaluated in a “phase 3” final human trial.

Returning to something like normal before the outbreak now relies on a combination of these late-stage vaccines that have been shown to be effective.

in a South AfricaThree of the most promising vaccines are being tested in cities across the country, with 2,000 participants testing a vaccine developed by the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford.

The study was recently halted after one person fell ill in the UK, but the trial has resumed with participants at Johannesburg’s giant Baragwanath Hospital who received the second part of this two-dose vaccine this week.

“Do you think this vaccine could work?” I asked Bonginkosi Ntombela, who lives in Soweto Town.

He replied, “I hope he succeeds, we must treat this disease.” “It takes a lot of our people, young and old, black and white.”

The man in charge of the Oxford trial, as well as the second Covid-19 A vaccine from the US company Novamax, called Professor Shabir Madi, and we found him circulating between a series of laboratories at the Paragwanath complex.

As part of his own global marketing campaign, Witswater University and the professor personally convinced vaccine developers to conduct clinical trials in South Africa and secured millions of pounds in funding to create the project.

“What we need to understand is that there is no rush on the part of pharmaceutical companies to do studies in Africa.

“Nothing at all. There’s very little incentive for them to come here. The only reason (the Oxford trial) is taking place in South Africa is because I went out to convince people that you need to do it now … and you can’t wait to do it after it passes.” Epidemic. “

The professor brings up the memory of an infection like swine flu when raising the issue of vaccine trials in Africa. Little research was done on this respiratory disease when it emerged in 2009, and by the time a usable vaccine was produced in Africa, the epidemic was virtually over. He says the same mistake should not be repeated.

“It will be a crime against humanity and a crime against the people of Africa if a mechanism for introducing vaccines is not put in place at the time of the pandemic rather than after its end – especially if we can prove that vaccines do indeed work.”

However, the battle against the virus will not only be fought in the laboratory. Sociologists from the University of Witswater ask members of the public if they will take an impact Covid-19 Vaccine.

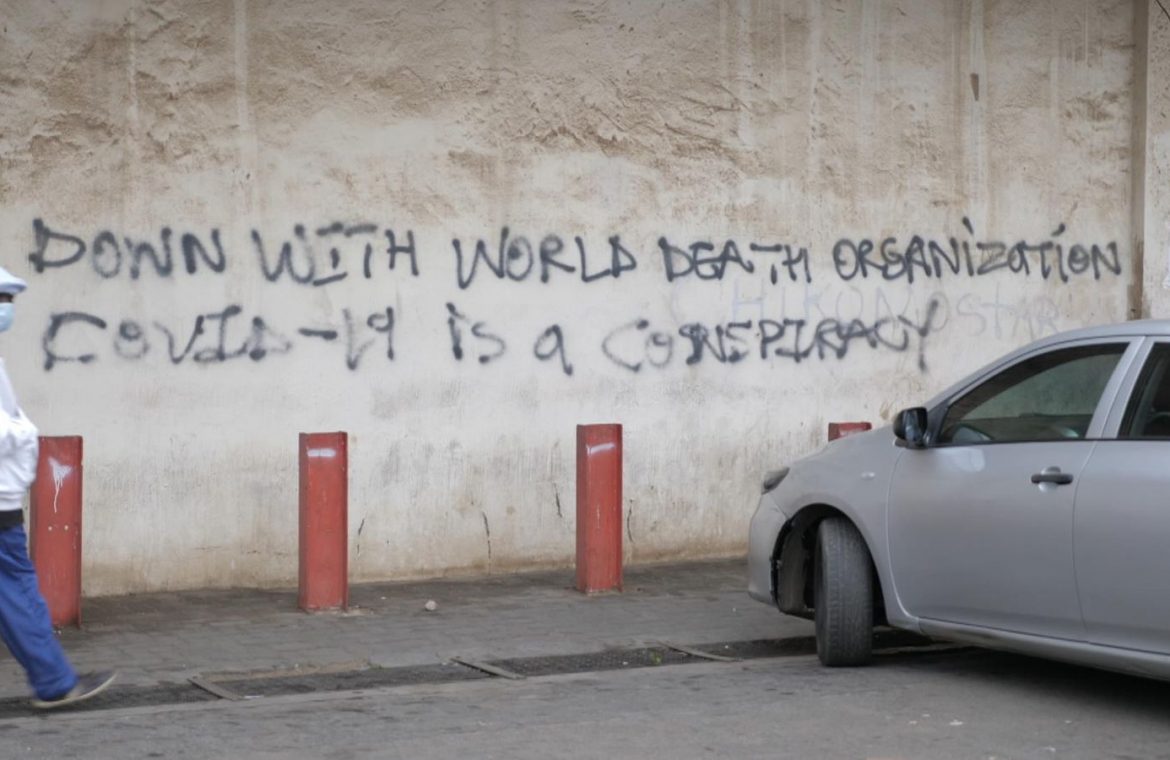

In South Africa alone, there are many myths and misconceptions about the virus that are routinely presented on the streets and social media.

One of these theories was put forward in the clinic at Paraguanth Hospital by a 19-year-old student named Chantelle Mangani.

Explaining why her friends and neighbors reject the COVID-19 vaccine, she said there is a common view that the virus is choosing its prey.

“To be honest, we have a mindset that this disease only takes white people and things … They are trying to say that this disease can see, and it can feel, if you have money, it attacks you. If you are poor then it cannot come because it knows you are You have no money. “

Researcher Noni Mjwenya, of the University of the Witswaterand, says such stories are created in an effort to understand something that is poorly understood.

“They feel that it is not realistic that whoever invented (the virus) brought it here to kill the people of South Africa … (People) think that things are set out to reduce the population of Africa.”

:: Subscribe to the daily podcast on Apple Podcast, Google Podcast, Spotify, speaker

The deep levels of suspicion and distrust aimed at developing a COVID-19 vaccine are not unique to South Africa. It is part of a global phenomenon, supported in part by amateur theorists on social media.

Challenging them through community awareness campaigns may become as important as introducing the vaccines themselves.