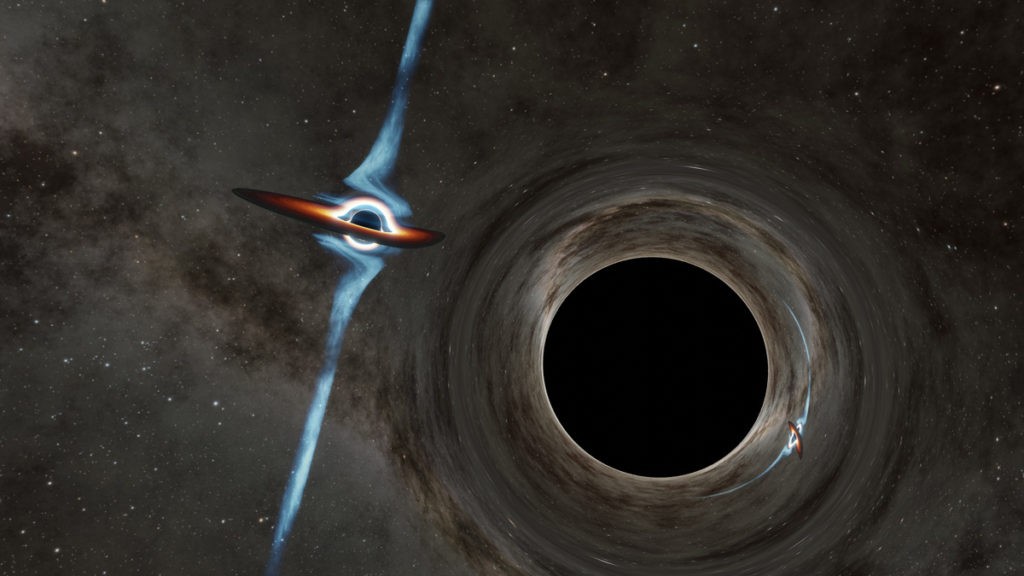

Technical view of a binary system of supermassive black holes in a quasar PKS 2131-021

Caltech / R. Wholesaling (IPAC) Photo

A publication appeared in the scientific journal “Astrophyscial Journal Letters” describing the recent discovery of a unique pair of supermassive black holes at the center of a distant active galaxy. One of the co-discoverers is Dr. Przemyslav Mroz of the University of Warsaw Astronomical Observatory.

The Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw reports that an international team of scientists has provided evidence of a pair of supermassive black holes in the center of a galaxy called PKS 2131-021 away from Earth about 9 billion light-years away. Two supermassive black holes, each hundreds of millions of times the mass of the Sun, orbit each other for about two years. This “cosmic dance” is the source of massive gravitational waves, the emission of which causes the distance between black holes to rapidly reduce. It is estimated that they will collide and merge in just 10,000 years.

PKS 2131-021 is a quasar, i.e. an active galaxy that emits a very large amount of electromagnetic radiation. Astronomers believe that at the center of each quasar is a huge black hole that sucks gas as it falls on it. Some quasars form jets, which are streams of material ejected from the quasar at nearly the speed of light. The galaxy under study belongs to a small subgroup of quasars, called blazars, the flow of which points toward the observer on Earth. Quasars emit electromagnetic radiation in a wide range – from X-rays, through light radiation, to radio waves.

In an article recently published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, scientists argue that there is not a single black hole in the center of the PKS 2131-021 galaxy, but a system of two supermassive black holes that have orbited each other for about 2 years. Years (For comparison, a comet found 2,000 AU from the Sun, orbiting around it for 90,000 years.) The movement of black holes causes the jet stream to change its position, causing periodic changes in the galactic radio brightness. Such differences in brightness were detected in archival data collected by three US radio observatories: the Owens Valley Radio Observatory (OVRO), the University of Michigan Radio Astronomy Observatory (UMRAO), and the Haystack Observatory.

When we realized that historical data collected over the past 45 years showed periodic changes in the brightness of the quasar, we realized that it was a unique object. Quasars usually have a chaotic variety, and this body glows and fades on a regular basis.

Dr. Przemyslav Mroz of the University of Warsaw Astronomical Observatory, co-author of the publication and responsible for mathematical modeling of the quasar light curve

An animation explaining the course of the phenomenon

Supermassive black holes are believed to be in the centers of all galaxies, including the Milky Way. When galaxies merge, which is relatively common in the young universe, the black holes at their centers must mate and eventually merge. This process must be accompanied by the emission of gravitational waves. So far, this theory has not been observed by observation. The discovery of a pair of supermassive black holes in the galaxy PKS 2131-021 offers hope that that will soon change.

Gravitational waves were first detected directly by the LIGO and Virgo observatories, in which astronomers from the University of Warsaw participated in the work. The supermassive black holes at the center of the galaxy PKS 2131-021 are tens of millions of times larger than the black holes discovered by LIGO and Virgo. The gravitational waves they emit have a frequency much lower than can be detected by LIGO and Virgo, but they can be detected by careful observations of pulsars. The authors of the publication estimate that the discovery of a pair of black holes in the quasar PKS 2131-021 should be confirmed in the next few years by experiments using pulsars to search for low-frequency gravitational waves, such as the European Pulsar Timing Array (EPTA) or the Nanohertz Gravitational Wave Observatory in America Northern (NANOGrav).

“We know of a very small number of confirmed supermassive black holes orbiting each other, and the newly discovered object has the shortest orbital period of them” – says Asok. Szymon Kozłowski of the University of Warsaw Astronomical Observatory, is an expert in the field of quasar anisotropy. “It’s something very interesting and unique!” – He adds.

source: University of Warsaw Astronomical Observatory